About Beaver Island

Beaver Island is a critical stopover site for migratory birds flying over Lake Michigan to

breeding grounds. This island is especially important to migrants flying into unfavorable weather conditions such as fog, heavy precipitation or strong winds from the north. Birds find a diverse mix of habitats on Beaver Island containing a wide variety of insect food. Insects such as midges are crucial to Neotropical migrants because the birds must regain resources lost during long flights over the Gulf of Mexico to be in prime condition for the rigors of breeding.

The BIBT includes examples of each of the Island’s diverse habitats along more than 100 miles of roads. Birding during spring migration (mid-to late-May) is excellent. During breeding season, nesting Osprey and Common Loon pairs can be observed easily without disturbing the birds. Many songbird species nest here, including a host of warblers, thrushes, flycatchers, tanagers and others. Fall birding is equally productive. During the winter it is not uncommon to view Snowy Owls, Pine Grosbeaks, and Rough-legged Hawks who venture south.

Native American History

“The archipelago of Beaver, High and Garden Islands in Lake Michigan has a long, deep history with the Odawa of Waganakisisng, or Odawa of the Land of the Crooked Tree. The Waganakising Odawa have traditionally called Emmet County home for centuries, but their home also included the Great Lakes themselves. Renowned for their skill at navigating the Great Lakes in trade and fishing and going on the war path, the Odawa counted thousands of islands in the Great Lakes as critical to their cultural, historical and economic identity. The Beaver Islands are very much related to the Odawa, past and present.

Beaver, High and Garden Islands were home to multiple Odawa villages, well into the 20th century. Fishing was a critical resource for these Odawa families because it provided food as well as income. Churches, schools and homes built by the Odawa were commonplace on these islands, just as they were on the mainland of Waganakising. The islands were so important to the Odawa at Waganakising that they requested the islands be included in the Washington D.C. treaty of 1836 as part of their homelands. This treaty was the first major treaty between the northern Michigan Odawa and the United States.”

–Repatriation, Archives and Records Department for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians

The Beaver Island Birding Trail acknowledges the land we serve as the traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg Tribal nations, ceded under the Treaty of Washington, signed in 1836. We also acknowledge the Tribal governments and their roles today in taking care of these lands.

For more information about the Native American presence on Beaver Island, visit the Beaver Island Historical Society’s Mormon Print Shop Museum on Beaver Island. Museum hours can be found at https://www.beaverislandhistory.org/.

Beaver Island

Beaver Island is the largest island in Lake Michigan with a total area of approximately 56 square miles. It is part of the Beaver Island archipelago which includes High, Hog, Garden and other smaller islands. The island is outstanding for its ecological richness. Sand dunes, sand beaches, cobble beaches, inland lakes, wetlands (including bogs with floating mats, Great Lakes marshes, and inland marshes), hardwood forests, conifer forests, old fields and other habitats support many plant and animal species.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recently designated an international biosphere in northern Michigan. The Obtawaing Biological Region includes preserved lands of the Beaver Island Archipelago as well as similar preserved areas on the mainland. The creation of this biosphere will foster cooperation among groups that manage preserved lands, such as the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, the National Park Service, and the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians.

In 2021 the Beaver Island Dark Sky Project filed an application with the International Dark Skies Association to designate approximately one-third of the island as a Dark Sky Sanctuary. Dark skies not only offer the opportunity to view celestial objects under ideal conditions but are also important to the biological functioning of animals and plants. Because many birds migrate at night, maintaining dark skies enhances their ability to navigate during migration and to locate stop-over sites such as Beaver Island.

Island Botany

Beaver Island’s 56 square miles encompass almost every type of habitat found on mainland Northern Michigan. The ability to visit so many habitats in such a short distance is yet another reason to enjoy Beaver Island.

Ecologically, Beaver Island is classified as part of the Northern Hardwoods– Beech Present plant community. This means that many of the hardwood forests on the island consists of American beech (Fagus grandifolia), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), and black cherry (Prunus serotina). An excellent example of this type of forest surrounds much of Fox Lake in the middle of the island.

A second forest type on Beaver Island is the Dry Mesic Northern Forest consisting of white pine (Pinus strobus), red pine (Pinus resinosa), red maple (Acer rubrum), northern red oak (Quercus rubra var. borealis), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), and big-tooth aspen (Populus grandidentata). This forest composes the inland part of the Bill Wagner Campground on the east side of the island and is considered a threatened natural community by the DNR’s Michigan Natural Features Inventory. Another interesting forest community on the island is the Conifer (Cedar) Swamp, consisting of white cedar (Thuja occidentalis), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis). A good example of this community can be seen at Little Traverse Conservancy’s Little Sand Bay Preserve on the east side of the island.

Other unique plant communities are found in Beaver’s bogs and on the island’s beautiful beaches. Many of the inland lakes are partially surrounded by bogs, which are defined as wetlands with little or no drainage and moisture provided by precipitation. The harsh environment of bogs has led to the evolution of plants that can tolerate waterlogged roots, acid conditions, and low nitrogen in the substrate. Some of these plants are carnivorous, capturing insects by various means to provide needed nitrogen. Common carnivorous bog plants on Beaver are the northern pitcher plant (Sarracinea purpurea) and several species of sundews (Drosera). There are also orchids in the bogs that bloom throughout the spring and summer, including dragon’s mouth (Arethusa bulbosa), grass pink (Calopogon tuberosus), and rose pogonia (Pogonia ophioglossoides). These plants can be seen in the Fox Lake bog on the southeast side of the lake and in the fen (a slightly different type of wetland from a bog) on the southeast side of Barney’s Lake along Barney’s Lake Road.

Many Beaver Island beaches are sandy, or sand mixed with gravel and rocks deposited by the wave action of Lake Michigan. These habitats are generally dry and hot in the summertime, and the substrate contains few nutrients that support plant growth. These environmental features also lead to plants adapted to withstand harsh conditions, and some of these plants have a very limited distribution around the Great Lakes, including on Beaver Island. Because of their restricted occurrence, several of these species are listed as federally threatened and should not be disturbed. Two of these species very likely to be observed along Beaver’s sandy shorelines are Pitcher’s, or beach, thistle (Cirsium pitcheri) and Lake Huron tansy (Tanacetum huronensis). Excellent beaches for observing these plants are found at the Bill Wagner Campground on the east side, Little Traverse Conservancy’s Petritz Preserve on the northeast side, and McCauley’s Point (state land) on the northwest side of the island.

A federally endangered species with a limited distribution on Beaver Island is the Michigan monkey-flower (Mimulus michiganensis). This plant grows only on the wet banks and in the water of muddy or sandy free-flowing streams. When the Michigan monkey-flower is not in flower, it is difficult to distinguish from other aquatic plants with which it grows, but its bright yellow flowers are unmistakable when it flowers in late June and July. The Michigan monkey-flower can be observed in the stream at the end of the trail at Little Traverse Conservancy’s Little Sand Bay Preserve.

Other plants of interest on Beaver Island are more generalized in their habitat choice and can be found growing along roadsides, in ditches, and in open fields and woods on the island. In the spring and early summer, residents and visitors alike delight in the three species of lady’s slipper orchids that grow in various patches along the Kings Highway. Yellow lady’s slippers (Cypripedium calceolus), pink lady’s slippers (Cypripedium acaule), and showy lady’s slippers (Cypripedium reginae) may be visible from the road. Two other species that put on a colorful roadside display in early to mid-summer are oxeye daisies (Leucanthemum vulgare) and the brilliant yellow Coreopsis lanceolata. A unique spring flower that grows in open wooded areas is the small, fuchsia-colored fringed polygala (Polygala paucifolia), and a beach plant with the wonderful name of hairy puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense) brightens the sand with clumps of intense yellow flowers in late May and throughout June.

All of the plants and habitats described are readily visible from different locations along the Beaver Island Birding Trail. So if your neck is getting tired and your eyes strained from looking up for birds, look down for a while at the interesting and unique natural plant communities under your feet or beside your tires.

–Dr. Edwin Leuck, Professor Emeritus of Biology

Herpetology of the Beaver Archipelago:

Amphibians and Reptiles of the Beaver Archipelago

The Beaver Archipelago boasts a diversity of amphibians and reptiles (“herps”). Following the theory of “island biogeography,” the number of herp species on any given island varies with the island’s size and its distance from the mainland, with Beaver Island possessing more of these species than all the other islands in the archipelago. However, although the Beaver Archipelago has fewer herp species than the Michigan mainland the population densities for any given species are higher in the archipelago than on the mainland. It is therefore comparatively easier to observe these species within the archipelago than on the mainland. Of the amphibian and reptile species in the Beaver Archipelago, eleven are amphibians (7 frogs and toads and 4 salamanders) while the reptile species list consists of 2 turtles and 8 (maybe 9) snakes.

The smallest frog is the spring peeper while the largest is the American bullfrog. The spring peeper is the first frog to be heard in the spring and is often heard in the fall as the photoperiod shortens. The bullfrog is the rarest of the Beaver Archipelago frogs, and may even be extirpated from the islands at this time, partially due to their being sought after as a culinary delicacy. The green frog, often varying in color from brownish green to blue, is by far the most common frog in the archipelago. Leopard frogs can be found in island wet meadows, gray tree frogs are ubiquitous across the islands, wood frogs occur in and around the islands’ forests, and the American toad will show up almost anywhere.

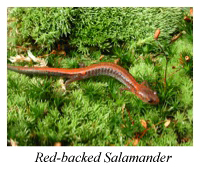

The most common salamander is the red-backed salamander which can reach densities of over 1000 per acre in the moist forests that they inhabit. The spotted salamander and blue-spotted salamander are much larger than the red-backed salamander. Because these two species are excellent burrowers, they are often known as mole salamanders. The last salamander found in the Beaver Archipelago is the eastern newt. It has a complicated life cycle where the larval form and adults are aquatic while an intermediate stage, the “red eft” is terrestrial.

The two turtle species found in the archipelago are the midland painted turtle and the common snapping turtle, which is the larger of the two species. Painted turtles on Beaver Island lay their eggs in the ground in June, and the young turtles hatch in early fall. However, these hatchlings remain in the shell in the nest, not emerging until the following spring. These nests may be as much as a half mile from their home pond or lake. On Beaver Island turtle mortality is often caused by unobservant motorists running over turtles in the road. Please watch for turtles on the island roads, especially during the spring and early summer months. If you do encounter a turtle and wish to help it cross a road, always move it in the direction it is traveling. Releasing a turtle back from the direction it came means the turtle may likely come back onto the road to continue its journey.

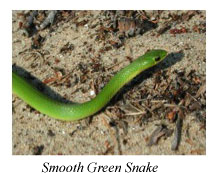

Of the eight species of snakes found in the archipelago, the largest by weight is the northern water snake while the largest by length is the eastern milk snake. The smallest is the red-bellied snake and its close relative, the northern brown snake. The smooth green snake is totally insectivorous and an egg-layer with one of the shortest incubation periods of any North American snake…nine days. The eastern ringneck snake is very aptly named with a well-defined ring around its neck, and feeds on salamanders. The eastern garter snake is the most abundant snake in the archipelago, and feeds on a wide variety of food, from earthworms to small mammals. The eastern ribbon snake, similar in appearance to the garter snake, is much more slender, with a longer tail. It feeds primarily on amphibians. Recently there have been sightings of a ninth snake species on Beaver Island, the eastern fox snake. This snake, which constricts its prey, grows to a length of 6 feet, making it the largest snake found in the archipelago. There are no venomous snakes on any of the islands of the Beaver Archipelago.

–Dr. James Gillingham, Professor Emeritus, Herpetologist, and Past Director of CMU’s Beaver Island Biological Station